Deficits...and a strong "cash position"

California's "cash position" among strongest of any subnational government in history

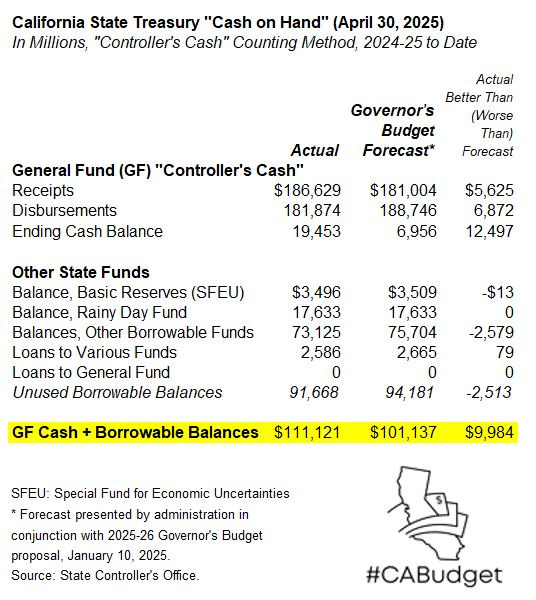

During the administration of Governor Gavin Newsom, California’s state treasury liquidity—loosely what one can think of as the state government’s “cash position” or “cash on hand”—has improved dramatically. On April 30, 2018, the year before he took office as chief executive, unused and available balances in state government funds totaled $35 billion. On April 30, 2025, these balances totaled more than $111 billion. (These state government balances do not include state and local pension fund holdings—for example, those of CalPERS and CalSTRS.) California’s current cash on hand is among the strongest for any subnational government’s operating funds ever.

The juxtaposition of the state’s formidable operating cash hoard with current and projected deficits—and the accompanying, difficult proposed budget cuts—is something I think about all the time. It is important to note that the administration wisely and prudently takes advantage of the strong state cash position to moderate its proposed budget cuts, as I will explain later. But, how did California state government get here? I will try to explain a bit in this long note.

Deficits Are Different When There’s a Cash Crisis

On November 30, 2008, the state treasury had less than $4.1 billion of available cash on hand—all of it borrowed from municipal bond investors. At the time, a 35-year-old LAO analyst—me—was assigned by very busy legislative budget staff to represent them at regular meetings of the Director of Finance and staff of the Controller and Treasurer to manage the state’s dire cash situation. Monitored closely by the White House and the Federal Reserve—who feared a California cash collapse worsening the dire crisis in the financial sector—these meetings were among the key experiences of my career. I learned a lot by being there!

One of several big state fiscal issues in late 2008 was a freeze on bond funds. This had little to do with balancing the deficit-ridden General Fund budget for the 2008-09 fiscal year, but it had everything to do with the state’s cash crisis. Prior to 2008, the state broadly used authority from a 1987 law, part of that year’s AB 55 (Roos), to provide advance funding from state treasury cash in anticipation of later bond issuance to fund capital projects and related staff work. As the state’s cash reserves dwindled to almost nothing in late 2008, “an obscure state financing agency, the Pooled Money Investment Board…was forced to preserve cash flow” by freezing payment “for some 2,000 projects funded by more than a half dozen voter-approved measures,” The Sacramento Bee’s Matt Weiser reported on December 24, 2008. “Near Placerville,” Weiser wrote, “long-sought park land might fall out of escrow…And in West Sacramento, officials fear a delay in rebuilding levees.” “The halted projects,” the Bee reported, “include an experiment involving 32,000 threatened Delta smelt, bred in a lab…Now scientists wonder how they’ll keep the fish alive.”

In budget subcommittee hearings that month, long lines of advocates lambasted the administration for the sudden bond funding halt. Governor Schwarzenegger blamed the Legislature for approving excessive budgets. “State Treasurer Bill Lockyer,” the Bee reported, “who voted his approval” as a member of the board, “called the action regrettable but necessary to preserve cash as the state general fund tumbles toward insolvency.”

The 2008-2009 cash crisis precipitated some of the hardest decisions of the dreadful 2009 state budget cycle, such as the bond funding freeze. Without warning, these big funding streams counted on by contractors, local governments, and non-governmental organizations were abruptly cut off. There was no rainy day fund, and there was a dwindling supply of state cash that had to be preserved to make sure bond debt service and state payroll were paid each month.

Bond debt service is contractually obligated, but also essential to pay on time since borrowing from the bond markets can be a key tool for managing a period of public budget distress. Bond market trust is essential for public budgeting. Salaries have to be paid on time for most state workers to keep basic state services going and avoiding large late payment penalties under labor laws.

A New Period of Responsible State Budgeting

In the years after the cash and budget crises of the Schwarzenegger years, Governor Brown and the Legislature benefited from a growing economy and stock market. They worked diligently to improve the state’s financial health, advocated voter approval of Assembly Speaker John Pérez’s rainy day fund proposal (ACAX2 1 of 2014), and changed to a more conservative manner of state budgeting that emphasized multiyear forecasting and used portions of projected surpluses for one-time spending, not just ongoing commitments and restorations. In August 2019, Legislative Analyst Gabe Petek wrote about the “quiet transformation of California’s cash management” over the prior decade. In December 2018, marking the tenth anniversary of the state’s cash crisis, his office released a report noting “the state has made undeniable progress” that “few could have predicted” a decade before.

The COVID pandemic seemed to threaten that progress, but federal fiscal and monetary stimulus produced instead a boom of sorts for the economy and state budget that brought new opportunities and challenges. In February 2025, I wrote about how the big COVID surpluses turned into projected deficits in recent years.

But, even amidst the challenges of recent years—when General Fund expenditures have been outpacing revenues, leading to draw down of about half of the state’s rainy day fund since 2024—the state’s cash position has remained very strong. And, as of April 2025, the state treasury’s health stands at one of its strongest points ever. How can that be? How is there so much money in the state treasury?

What’s in the State Treasury?

The state treasury principally is held in the Pooled Money Investment Account (PMIA), managed by the State Treasurer’s Office under the direction of the Pooled Money Investment Board. The $111 billion I mentioned as of April 30, 2025, comes from cash balances in the General Fund ($19 billion after April tax collections), the General Fund’s basic statutory reserve (known as the Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties, or SFEU, with more than $3 billion), the state’s main rainy day fund (known as the Budget Stabilization Account, or BSA, with about $18 billion), and then the balances on hand of all the other state budget accounts, which total a staggering $73 billion—largely balances from the state’s many “special funds.”

In the PMIA, state funds—plus some local governments’ balances held in separate accounts—are invested in safe, liquid instruments, primarily U.S. Treasuries. As of April 2025, the PMIA’s average yield was 4.281%.

Visibility on which state funds in the PMIA have big balances is hard to get in real time, but as of June 30, 2023, the most recent state “budgetary/legal basis annual report” (the BLBAR) lists dozens and dozens of state funds and their state treasury and agency account cash balances, as well as deposits in the Surplus Money Investment Fund, a part of the PMIA (starting on page 32 here).

Based on my experience, I observe that these state balances collectively have grown for the following reasons in recent years:

State departments under the Governor’s direction, which manage the accounts day to day, budget much more conservatively than in the past, I believe.

Departments disburse budgeted funds slowly in some cases, especially relating to delays in filling positions and expending funds for large one-time projects, such as those approved in budgets of recent years.

In a limited number of cases, special fund fee levels are arguably too high, a perennial problem that legislators and stakeholders sometimes discuss with relevant state departments.

The growth of state General Fund reserves, including the rainy day fund, is a new thing over the last decade.

Note that there are some state accounts listed as “outside the state treasury” in the BLBAR (starting at page 486 here), such as some of the California State University system. The University of California is a separate constitutional entity and also manages its own investments.

How Does the Deficit Relate to All This Cash?

The state accounts for all of its many, many accounts separately. The California Constitution has special rules for the accounting of State Fund Number 0001, the General Fund, which is the principal operating fund for state government. The Constitution requires the following with regard to the General Fund:

“From all state revenues there shall first be set apart the moneys to be applied by the State for support of the public school system and public institutions of higher education.” This declaration precedes the key features of Proposition 98, which specifies the annual minimum funding guarantee for public schools and community colleges. (Article XVI, Section 8)

Debt service for general obligation bonds is effectively the next priority for General Fund moneys, as specified in each such bonds’ offering statements. The state’s general obligation bond law creates an obligation that is “irrepealable until the principal and interest” of the bond “shall be paid and discharged” (Article XVI, Section 1). In practice, debt service for other bonds is treated similarly for budgeting.

The General Fund has a specific balanced budget requirement in the Constitution. Beginning in 2004, following passage of Proposition 58 (2003), “the Legislature may not send to the Governor for consideration, nor may the Governor sign into law, a budget bill that would appropriate from the General Fund” more appropriations for a fiscal year than the amount of revenues, including rainy day fund withdrawals, available to the General Fund (Article IV, Section 12[g]). Section 35.50 of the annual budget act specifies the official revenue estimate for purpose of this provision (as proposed in the recent May Revision on page 8 here). The amount in subsection (b) of Section 35.50 typically is the fiscal year’s revenue estimate plus available fund balance estimated to remain in the General Fund at the end of the prior fiscal year.

Under these rules, the General Fund’s shortfall is accounted for separately from all the other state accounts, and it can only take advantage of the part of the rainy day fund able to be withdrawn under constitutional rules. So, that’s why there is a projected deficit for 2025-26 despite all the cash on hand in the state treasury.

Under the rules, the state’s strong cash position definitely helps moderate required cuts to balance the General Fund budget this year. For example, under the May Revision proposal for Section 35.50, $34 billion of estimated General Fund balances at the end of 2024-25 is able to be spent on 2025-26 state expenses. This $34 billion consists of cash projected to be in the treasury at the end of 2024-25, as well as receivables (including many billions of dollars of later tax collections that will be accrued to 2024-25) and other assets. Moreover, the planned use of $7.1 billion of the projected $18.3 billion rainy day fund balance at the end of 2024-25 helps moderate cuts.

Cash Balances Expand Toolkit to Balance Budget

Every time that the budget has a projected deficit, Governors and legislators agree to use balances from outside the General Fund—principally from the state’s “special funds”—to help balance the budget. This is one way to temporarily delay more difficult budget actions, such as program cuts or tax increases. It is a very important way that the state’s strong cash position helps address projected deficits.

California case law gives the Legislature broad authority to loan available special fund balances to the General Fund to help address projected deficits. Special funds typically receive money from fees, such as user fees or license charges, dedicated to a specific state department’s services to the public. Courts have given the Legislature significant flexibility to decide when special funds lend money to the General Fund and when and how the loans are paid back. In Daugherty v. Riley, 1 Cal.2d 298 (1934), the state’s Supreme Court suggested that special funds could be loaned to the General Fund, so long as the funds are returned to the special fund “as soon as funds are available” and the loan does not interfere “with the object for which the special fund was created.” In California Medical Assn. v. Brown, 193 Cal.App.4th 1449 (2011), the appellate court cited the 1934 Daugherty decision in allowing a loan from the Medical Board of California’s Contingent Fund to the General Fund. In Tomra Pacific, Inc. v. Chiang, 199 Cal.App.4th 463 (2011), an appellate court noted that special fund loans may cause some negative impacts on programs, but a “practical approach is necessary” that allows “the state sufficient ‘flexibility to balance its budget.’”

In 2024, the state budget included $2.1 billion of loans and loan extensions (extensions of prior loans’ repayment dates) from special funds to help balance the 2024-25 state budget. The 2024 budget plan aimed to balance the budget over two fiscal years, and it included an additional $683 million of loans and extensions to balance the 2025-26 state budget. Subsequent revenue and spending projections have resulted in a projected $11.9 billion deficit, and the Governor’s recent May Revision proposes added loans of $550 million from two state special funds. The May Revision also proposes extending the period to pay for the recent $3.4 billion General Fund loan to a special fund supporting the Medi-Cal program to June 30, 2034 (see proposed Provision 22, Budget Item 4260-101-0001, page 22 here).

The state’s strong cash position also facilitated a multiyear fiscal maneuver in 2024 to recognize $6.2 billion of 2022-23 Proposition 98 expenditures in budgetary accounting over ten years beginning in 2026-27.

It is only because of the state’s extraordinary cash position that it can funnel billions of these special fund dollars to help balance the General Fund budget now.

Helpful, But Not a Panacea: Cash Can’t Balance the Budget Forever

So, if the state’s cash position is so strong, why are such difficult budget cuts and even some tax increases needed now? Basically, it comes down to this: an ongoing imbalance of revenues and expenditures eventually would consume all the cash. Cash cannot balance the budget over a long period.

After passage of Proposition 2 in 2014, the state’s annual budgeting process changed to focus much more on the multiyear financial projection that measure requires. For the recent May Revision, the administration’s updated multiyear projection is here.

Even if all of the Governor’s May Revision budget cuts and other proposals are adopted, that projection estimates that the General Fund would be $41.5 billion in the red at the end of 2028-29 (the projected negative SFEU “basic reserve” balance). Consider, however, what the projection was like before the administration put the Governor’s May Revision proposals on the spreadsheet. Under the May Revision estimates, the Governor’s new budget-balancing proposals add up to a cumulative amount of $55.5 billion through 2028-29. Accordingly, I guess that the SFEU balance would have been about $97 billion in the red before considering the Governor’s May Revision proposals (that is, $41.5 billion plus $55.5 billion).

While the $73 billion in non-General Fund cash balances now reported in the state treasury are very helpful, they are there in part due to delays in disbursement and temporary phenomena. To cover all of the possible $97 billion in deficits from special fund and other state treasury cash through 2028-29 would be unwise and ill-advised. Using too much cash on hand to balance the General Fund now would put the operation of borrowed special funds at risk, among other problems.

In the end, revenues and expenditures of the state will always differ from the projection, and the decision of how much or how little to balance the budget now from non-recurring sources like cash balances is a subjective one.

But, having big cash balances in the state treasury: it’s much better than having small cash balances. California has learned that lesson over the last two decades.