From big surpluses to projected deficits...

Responding to questions on how California's budget situation evolved in recent years

People frequently ask how California’s state budget went from record projected surpluses to a future outlook of structural deficits over just a few years. This note responds to that question. A summary of key points is provided, followed by more historical detail for those who are interested. (A full version of this post is available on my Substack page if this post is cut off in your email due to length.)

Key Points

The state budget was in good shape, with big reserves, when the COVID pandemic began.

Federal fiscal and monetary stimulus contributed to big growth in tax revenue between 2020 and 2022.

In budgeting projected surpluses during the pandemic, state leaders prioritized one-time costs, such as infrastructure projects (often over a multiyear period) and tax rebates.

A 1979 constitutional amendment, the Gann Limit, made it easier to budget for infrastructure and tax rebates and harder to set aside surpluses in reserves, especially in 2022.

The state implemented various increases in ongoing spending, especially in 2021 and 2022, such as expanding Medi-Cal, increasing child care spending, boosting developmental services provider payments, and increasing university funding. These costs were estimated to grow over time in multiyear budget forecasts.

In 2022, the budget anticipated a modest drop in revenues after a very strong 2021-22 fiscal year. State budgets rarely assume drops in revenue absent a recession, so the 2022 forecast was, on one level, a conservative projection. In retrospect, however, the 2022 forecast was not nearly conservative enough. Revenues dropped a lot more than projected in 2022-23.

The U.S. experienced a short recession as unemployment rose in early 2020, but federal stimulus helped prevent a U.S. recession thereafter during the pandemic. Nevertheless, key sources of California tax revenue—the stock market and technology initial public offerings—experienced sharp downturns starting a few weeks before the 2022 budget was passed. Higher interest rates and inflation contributed to these drops. In retrospect, we know that real gross domestic product in California declined in three of the four quarters in 2022 and in the Bay Area for calendar year 2022, indicative of what might be considered a “regional recession” at the time.

The full extent of the 2022 revenue downturn did not become apparent until the 2024 budget cycle because a series of storms in December 2022 and January 2023 caused the IRS to delay many required payments by high-income California taxpayers for an unprecedented 10 months. The 2023 budget had to be passed with an unprecedented lack of real-time data about these taxpayers’ payments.

In 2024, the Legislature and the Governor agreed to balance the budget over a two-year period (2024-25 and 2025-26), using about half of the state’s main rainy day fund. Reductions and delays in one-time spending (including natural resources and environmental spending) were implemented, as were temporary reductions in school spending and a temporary, three-year increase in certain business tax payments.

The 2024 budget plan anticipated sizable deficits after 2025-26 due to remaining one-time spending obligations, the expiration of temporary business tax increases, and growth of recent ongoing spending commitments. Moreover, the Proposition 30/55 taxes on upper-income personal income tax filers—providing more than $10 billion of annual state revenue currently—expires in 2030.

Some recent ongoing spending commitments, including health care costs, have been growing faster than projected previously, consistent with inflation in the overall economy. This contributes to future projected state General Fund deficits of well over $10 billion per year.

Threatened cutbacks in federal spending in 2025 might increase projected deficits. Big downturns in stock prices, the technology sector, or the overall economy also could increase projected deficits.

Historical Detail

Background

Volatile Tax Structure, Much of It Voter-Approved. California state budgeting constantly manages changing projections of its volatile personal income taxes, which go up and down due to changes in the stock market and technology industry that are amplified by the state’s progressive tax rate structure. Key parts of that tax rate structure have been embedded in the State Constitution by voters. To address the volatility, Assembly Speaker John A. Pérez proposed ACAX2 1 in 2014, a new state rainy day fund later passed by voters as Proposition 2.

Structural Deficit Forecasts: Common in California. Forecasts of persistent, future deficits have been common in California state budgeting for decades, in part due to episodic declines in those volatile tax revenues. While Legislative Analyst’s Office (LAO) fiscal outlook publications have changed over the years, more than half of the last 30 LAO November outlooks have projected future deficits. All but one of the LAO November outlooks in the 2000s projected future deficits, and so have all but one of them during the 2020s so far. California’s state legislators and the Governors nevertheless must balance each year’s annual budget, according to constitutional rules that were tightened by voters at the March 2004 election, just a few months after the recall of Governor Davis.

Pre-Pandemic: Budget in Good Shape

State Budget Entered COVID Pandemic in Good Shape. The 2010s were a rare recent period of stability and growth for California state finances. The 2010s were marked by increased revenues due to voter approval of Propositions 30, 39, and 55 and general economic growth, as well as the growth of the voter-approved rainy day fund (originally ACAX2 1 of 2014). As a result, the state budget entered the COVID-19 pandemic in fairly healthy shape. A December 2018 LAO publication, The Great Recession and California’s Recovery, described the state government as “much better prepared for a recession” than it was during the 2000s. The LAO’s November 2019 Fiscal Outlook projected the state had a possible “ongoing surplus of around $3 billion” and a rainy day fund of over $16 billion—near its constitutional target of 10 percent of General Fund tax revenues.

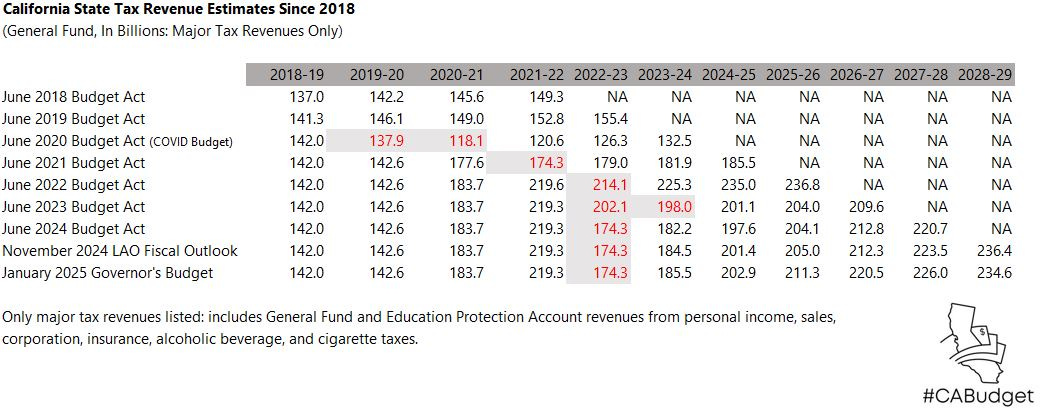

2020: The COVID Budget

Very Cautious Budget Crafted in Opening Months of Pandemic. California’s first COVID-19 cases were identified in late January 2020. Governor Newsom issued a statewide “stay at home” order on March 19, 2020. During the spring, Congress began passing legislation to bolster the economy against widespread unemployment. Economic uncertainty during this period was thought to render the Governor’s January 2020 budget proposal, with its forecast of a multibillion-dollar surplus, obsolete. The Governor’s May Revision in May 2020 and the June 2020 budget act adjusted revenue projections down by more than $40 billion across the 2018-19 through 2020-21 period, as shown in Table 1 below. The June 2020 budget agreed by the Legislature and the Governor used $8 billion of reserves, deferred $12.5 billion in payments to schools, adopted $8 billion of spending cuts (including state employee pay reductions), and other actions to address a $54 billion budget deficit that year.

June 2020 Multiyear Forecast: Substantial Deficits Ahead. While the June 2020 budget act balanced the budget for 2020-21, as required by the State Constitution, substantial future operating deficits were projected at the time, ranging from $9 billion for 2021-22 to $18 billion for 2023-24.

2021: Soaring Revenues

Revenues Begin to Soar. As it turned out, the 2020 budget was quite cautious. As shown in Table 1 (June 2021 Budget Act and later estimates for 2020-21), revenues soared above expectations. This occurred due to the robust federal fiscal and monetary stimulus related to the pandemic. The 2021 May Revision identified a $38 billion discretionary surplus for that year’s budget process. That surplus was adjusted to $47 billion in the June 2021 budget package. As LAO noted, the 2021 “spending plan dedicates the vast majority—nearly $39 billion—to one-time or temporary program augmentations,” such as $8.1 billion in state stimulus payments to low-income Californians. Transportation and drinking water and drought infrastructure programs were other large recipients of one-time spending.

State Stays Below Constitutional Appropriations Limit. The stimulus payments, along with infrastructure appropriations and various technical adjustments, kept the state budget under the constitutional State Appropriations Limit (SAL, also known as the Gann Limit, originally adopted by voters in 1979) despite robust revenue growth.

More Than $10 Billion of Ongoing Spending Commitments. The budget used $3.4 billion of the surplus for new, ongoing spending, the full implementation costs of which were projected by LAO to grow to $12.4 billion by 2025-26. Among these ongoing spending commitments were a multiyear plan to fund transitional kindergarten ($2.7 billion at full implementation), three major expansions to Medi-Cal eligibility (projected at $1.9 billion by 2024-25), increased developmental services provider rates (projected at $1.2 billion by 2025-26), child care slot and rate increases (more than $3 billion ongoing across state and federal fund sources), new state employee contracts (more than $700 million of ongoing General Fund costs), and about $500 million of new ongoing commitments to the university systems. The federal government’s American Rescue Plan Act provided $27 billion of fiscal relief funds to the state, which were initially allocated in the 2021 budget, generally to one-time purposes, including replacing what the act termed “revenue loss” due to the pandemic (see LAO Figure 7 here).

Rainy Day Fund Budgeted at $15.8 Billion. The rainy day fund—with revised balances of more than $17 billion prior to the pandemic—was budgeted at $15.8 billion in the 2021-22 budget package, recovering in part from its partial drawdown in 2020.

June 2021 Multiyear Forecast: Substantial One-Time Spending. The administration’s multiyear forecast as of the June 2021 budget act showed a $5 billion operating deficit for 2022-23 and relatively small annual deficits of $3 billion to $4 billion for the subsequent two years. For 2022-23, the forecast noted that $11 billion of programmed one-time spending could be delayed or cancelled, if needed, based on fiscal conditions.

2022: Big Estimated Surplus

Revenues Continue to Climb Into Early 2022. Federal stimulus continued to power the economy and tax revenues into early 2022. The May 2022 May Revision, “reflecting extraordinary revenue growth for a second year in a row,” allocated a $52 billion General Fund surplus, LAO estimated. As shown in Table 1, the June 2022 Budget Act forecast (generally reflecting that year’s May Revision) increased revenue estimates substantially. The robust revenue growth was estimated to bring the state budget up to the constitutional Gann Limit, and addressing SAL requirements was a major focus of the budget negotiations between the Legislature and the Governor.

June 2022 Spending Plan Allocated $55 Billion Estimated Surplus. LAO estimated the 2022-23 budget plan allocated a $55 billion overall General Fund surplus, based on updated estimates. The $55 billion included:

$36.3 billion of one-time or temporary spending, including substantial spending on environmental protection and transportation as part of multiyear investment programs.

$10.5 billion of revenue reductions and tax refunds, including the more than $9 billion Better for Families Tax Refund program (one-time payments to households with incomes up to $500,000).

$3.5 billion to the state’s main, discretionary budget reserve, the Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties. (In general, deposits to reserves are limited by the Gann Limit.)

$2.3 billion to ongoing spending increases, the costs of which were estimated by LAO to grow to $4.9 billion by 2025-26.

Ongoing costs in the budget plan included the expansion of Medi-Cal to the rest of otherwise eligible undocumented populations (with an expected cost of $2.1 billion General Fund per year at full implementation), several hundred million dollars of funding increases for the university systems and student financial aid, and accelerated implementation of developmental services provider rate increases.

$2.5 billion to pay off debts and liabilities.

Revenues Budgeted to Decline by 3%. Atypically for the state budget in a time of economic growth, the June 2022 state budget plan anticipated a decline in General Fund tax revenues in 2022-23. Specifically, a 3% decline was anticipated from the record levels of 2021-22 to a more modest 2022-23, as shown in Table 1.

Rainy Day Fund Budgeted at $23 Billion. The 2022 budget plan anticipated the rainy day fund would grow to an unprecedented $23.3 billion in 2022-23. Total reserves in the 2022 budget plan, including the Proposition 98 school rainy day fund, were budgeted at more than $37 billion.

June 2022 Multiyear Forecast: Substantial One-Time Spending. The administration’s multiyear forecast as of the June 2022 budget act projected a $16 billion operating deficit for 2023-24 and small deficits or surpluses in the two fiscal years thereafter. The forecast, however, noted that $22 billion of anticipated 2023-24 spending was one-time, with the anticipation it could be delayed or cancelled if fiscal circumstances required.

2023: Revenues Drop and Tax Receipts Delayed

Stock and IPO Market Deterioration Began By Mid 2022. As the administration’s May 2022 revenue estimates were being finalized, stock prices began to tumble. Specifically, between March 30, 2022 and June 16, 2022, the S&P 500 Index lost 20 percent of its value. U.S. stock prices remained depressed for most of the rest of 2022. “After years of easy money,” The Washington Post reported, “the Federal Reserve began raising interest rates in March to combat inflation and never stopped.” In addition, the initial public offering (IPO) market, a key means of generating wealth for tech investors, dried up in 2022, with proceeds of IPOs in the Americas reportedly dropping a staggering 95 percent below 2021 levels. “The dismal performances in equities throughout 2022, aggressive rate hikes from central banks and fears of a looming global recession all stymied activity,” S&P Global reported. Notably, these developments came too late to be fully incorporated into 2022 budget estimates, which, unusually, anticipated a decline in state revenues, but only a modest decline. By the end of December 2022, income tax revenues were beginning to fall far short of projections.

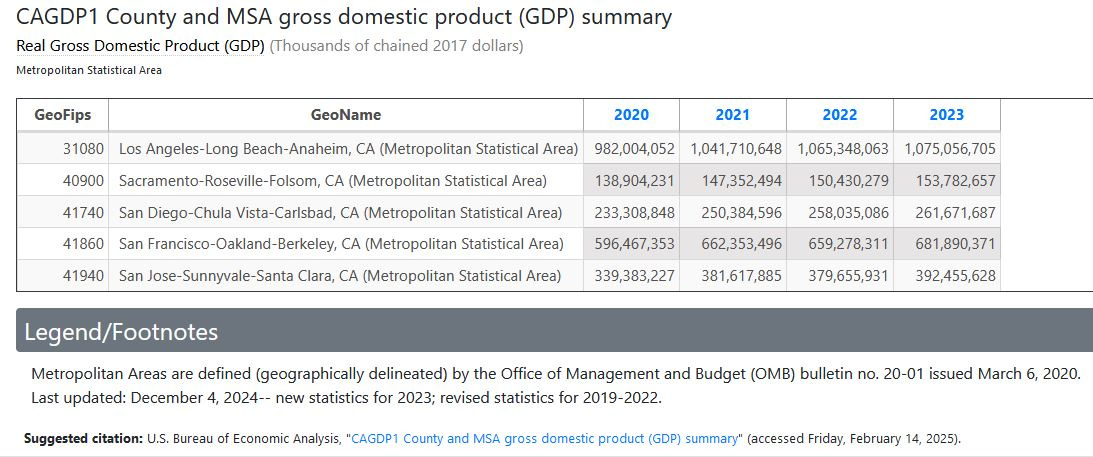

Parts of California Entered a “Regional Recession” in 2022. Consistent with the negative stock and technology sector trends noted above, we know in retrospect that the Bay Area entered what could be considered a “regional recession” in 2022. As shown in Table 2, real gross domestic product (GDP) declined slightly in the Bay Area in 2022. For the state as a whole, real GDP declined in the first, second, and fourth quarters of 2022.

Unprecedented Tax Delay Stymies Forecasting Efforts. A series of atmospheric rivers drenched most of California in December 2022 and January 2023, with almost all of the state receiving rainfall totals of 400 to 600 percent above average over a two-week period. In response, the U.S. Internal Revenue Service extended filing and payment deadlines for most individuals and businesses across California until May 15, 2023, and California’s Franchise Tax Board conformed with this federal delay. Eventually, the IRS’s delay was extended to November 16, 2023, meaning that many of the state’s biggest taxpayers paid nothing in income taxes for an unprecedented 10 months. This meant that the May Revision included no real-time data on those taxpayers’ status, greatly reducing the reliability of the May budget estimates.

Revenue Forecasts Lowered. As shown in Table 1, the June 2023 revenue estimates lowered 2022-23 and 2023-24 revenue estimates significantly, compared to those used in the June 2022 budget. As a result, according to LAO estimates, the Governor and the Legislature addressed a $27 billion budget problem in the June 2023 budget package.

Addressing the 2023 Budget Shortfall. As characterized by the LAO, the June 2023 budget package addressed the $27 billion budget shortfall as follows:

$13 billion in spending-related actions, including $6 billion in reductions (such as withdrawing a $750 million planned principal payment on state unemployment insurance loans to the federal government and a $549 million reduction to an energy arrearage payment program) and $6.7 billion in delays.

The LAO noted that despite these reductions and delays, “significant temporary spending is still authorized…for 2023-24 and beyond, including $12.5 billion in 2023-24, $9.4 billion in 2024-25, and $4.1 billion in 2025-26.”

$10 billion in shifts of costs from the General Fund to other state funds, including $2.7 billion in loans from special funds and $1.6 billion of costs shifted for zero-emission vehicles and other energy programs to the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund.

$3.6 billion in revenue-related actions, including a renewed tax on managed care organizations (MCOs), which draws down federal funds that offset General Fund costs.

Rainy Day Fund Budgeted at $22.3 Billion. The June 2023 budget plan budgeted the state’s main rainy day fund at $22.3 billion—with revised lower required deposits due to lower revenue estimates, but no withdrawal. Inclusive of all reserves, including the Proposition 98 school reserve, total reserves were about $37.8 billion.

June 2023 Multiyear Forecast: Significant Future Deficits. The June 2023 multiyear forecast by the administration showed significant operating deficits of $15 billion to $18 billion annually between 2024-25 and 2026-27. Even if all one-time investments were removed, the future annual operating deficits totaled $6 billion to $14 billion annually during that period.

2024: Two-Year Budget Plan, as Revenues Drop More

Late Tax Receipts Well Below Projections. The late tax collections in October and November 2023 fell more than $25 billion short of projections. As a result, the Governor’s January 2024 budget proposal addressed a $58 billion shortfall, according to LAO estimates—later revised to $55 billion in the May Revision. As shown in Table 1, the June 2024 budget act revenue estimates (based on the 2024 May Revision) lowered revenue estimates substantially for 2022-23 and 2023-24.

Addressing Projected 2024 and 2025 Budget Shortfalls. In the June 2024 budget package, the Governor and the Legislature decided to balance the budget over two years, using a partial withdrawal from the rainy day fund and other actions to bring the budget into balance for two years: an unprecedented decision for modern California state budgeting.

For 2024-25, the $55 billion of actions to address the annual shortfall included:

$5 billion drawdown from the main rainy day fund and a $900 million withdrawal from the Safety Net Reserve Fund.

$19 billion of adjustments to school and community college spending, including a suspension of the annual Proposition 98 minimum funding requirement and accruing $6 billion of prior payments to future fiscal years in the state accounting system (a new type of fiscal maneuver that avoided rescinding prior payments to schools).

$20 billion of other reductions, including $14 billion of cuts (such as $2 billion in annual ongoing reductions to state operations), $4 billion of fund shifts, and $2 billion of delays.

$2 billion of cost shifts, including $1.7 billion of new special fund loans to the General Fund.

$8 billion of revenue-related actions, principally by limiting medium and larger businesses’ use of net operating losses and certain tax credits for three years beginning in 2024.

For 2025-26, as described by LAO, 2024 moves to balance the budget included about $11 billion in spending-related actions, $5.5 billion from the continuing temporary revenue actions described above, a $7 billion additional withdrawal from the rainy day fund, and around $2.5 billion of other actions.

Partial Rainy Day Fund Drawdown. Constitutional rules would have allowed the drawdown of the entire state rainy day fund over two fiscal years due to the size of the revenue shortfall. Instead, the Legislature and the Governor agreed to draw down only about half of the rainy day fund over a two-year period. The 2024 budget plan anticipated a $4.9 billion net drawdown for 2024-25 and a $7.1 billion drawdown for 2025-26, which left an estimated balance of $10.5 billion at the end of 2025-26.

2025: Deficits Projected and Costs Rise

The Governor released his proposed 2025-26 budget on January 10. The administration projects the state would have $10.9 billion in the rainy day fund in 2025-26 and $17 billion in total reserves if the Governor’s proposals were adopted. Annual operating deficits of $13 billion to $19 billion per year are projected thereafter through 2028-29. Not reflected in that forecast are the future expiration of some key revenue sources, such as the expiration of the Proposition 30/55 tax on upper-income tax filers in 2030. That measure currently generates over $10 billion per year of revenue. The budget reflects some increasing state costs, such as 2024-25 General Fund Medi-Cal costs increasing about $3 billion above previous estimates and 2025-26 costs rising another $4.5 billion. The Governor will release his May Revision by May 14, and the Legislature must send a budget bill to the Governor by June 15.

Methodology Note. Throughout this piece, LAO citations of surpluses and deficits are used. LAO estimates often are calculated on a different basis from those of the administration—principally in how they reflect school funding amounts in some years. There are various ways that a surplus or deficit can be calculated in California budgeting. In and of themselves, different surplus/deficit estimates can reflect the same revenue and expenditure estimates of the state’s financial situation—just different ways of characterizing that situation.