State tax credits and exemptions now exceed $90 billion per year

Tax provisions reduce General Fund revenues, but many are popular and durable

In 2015, at the request of Senators Richard Pan and Loni Hancock, several LAO colleagues and I drafted this review of California state government “tax expenditures.” The term “tax expenditures” refers to tax exclusions, exemptions, preferential tax rates, credits, and other tax provisions that reduce the amount of revenue collected from the basic tax structure. Our 2015 review used Department of Finance (DOF) and tax agency data to show that California's estimated 2014-15 General Fund revenues “would be roughly 50% greater if there were no personal income, sales and use, or corporate income tax expenditures in state law.”

The largest tax expenditures in 2014-15 were direct subsidies to households for necessities, health coverage, home mortgage interest, and retirement benefits, with the six largest tax expenditures accounting for almost half of the total.

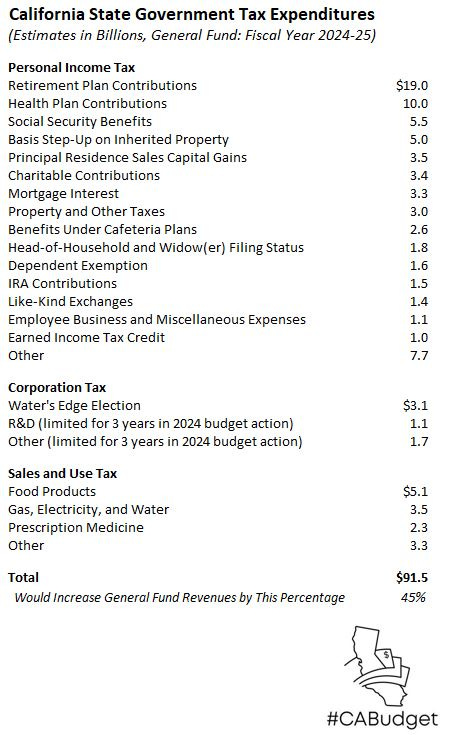

Updated Tax Expenditure Totals. Almost ten years later, I recently recalculated these figures using data from the most recent DOF Tax Expenditure Report. The result: California’s $204 billion of estimated General Fund revenues (excluding transfers) in 2024-25 would be roughly 45% greater if there were no personal income, sales and use, or corporate income tax expenditures in state law.

General Fund tax expenditures for 2024-25, as estimated by DOF, are summarized below and described in detail in the DOF report.

Largest Personal Income and Sales Tax Reductions: Durable and Popular. As shown above, the largest personal income tax (PIT) and sales and use tax (SUT) tax expenditures subsidize household necessities, health coverage, and retirement benefits. The three largest PIT and the three largest SUT tax expenditures, which all provide such subsidies, make up almost half of the statewide total. Obviously, these tax expenditures are durable and popular, as are many smaller tax expenditures.

Water’s Edge Election. The largest corporation tax (CT) tax expenditure is the water’s edge election provision of the Revenue and Taxation Code. This provision is notoriously difficult to explain, but it is useful to note that state corporate income taxation requires using formulas to determine what part of a corporate group’s income is attributed to each state. A water’s edge election means a corporation bases its California income tax liability on the state’s share of domestic, rather than worldwide, income, typically because that choice results in a lower tax liability. Under California law, the water’s edge election is generally for a seven-year period.

Research and Development (R&D) Credit. After water’s edge elections, the R&D credit is the second largest CT tax expenditure. The R&D credit subsidizes research expenditures, but there is little public information available on the specific corporate research subsidized by the state tax expenditure. R&D credit usage is reduced in 2024-25 due to a three-year limitation on the use of such credits in the 2024 budget package. According to DOF’s estimates, the amount of revenue loss due to the R&D tax credit fell from $1.9 billion in 2022-23 to an estimated $1.1 billion in 2024-25, largely as a result of the budget action. In general, credits foregone during the three-year limitation are expected to be used at a later date.

Basis Step-Up on Inherited Property. In conformity with federal tax law, California tax law sets the tax basis of property acquired by bequest, gift, or inheritance at the fair market value at the date of death, so that appreciation that occurred prior to the death is not taxed. This is one of the largest PIT tax expenditures.

What Is Not Listed. Determining what is a tax expenditure and what is a basic component of California’s tax system is subjective. As discussed on pages 7 and 8 of this year’s report, DOF excludes certain items from the tax expenditure lists, such as net operating loss (NOL) deductions, general corporate tax apportionment rules, and the tax treatment of Subchapter S corporations. Arguments could be made to include various such items as tax expenditures, which could add several billion dollars to the tax expenditure total. California’s state and local tax system, in total, is one of the nation’s most progressive, meaning that the top 1% of income earners pay a larger share of their family income than other income groups do—in large part due to voter approval of higher tax rates for the highest-income tax filers. DOF notes that the lower marginal tax rates for lower- and middle-income groups do not count as a tax expenditure on its list.

Proposals to Change Tax Expenditures. Legislators introduce bills to adjust tax expenditures in every legislative session. Proposals can involve the introduction of new tax expenditures, targeting existing tax expenditures to specific income or other groups, expanding tax expenditures to increase their value or provide their benefits to more taxpayers, or eliminating certain tax expenditures. Increased tax expenditures generally reduce General Fund revenues, and for every $1 of lowered revenues, Proposition 98 guaranteed school funding drops, typically by about 40 cents. Conversely, reduced tax expenditures generally increase General Fund revenues, with every $1 of increased revenue boosting Proposition 98 funding, typically by about 40 cents. Changes in revenues also reduce or boost required rainy day fund and related deposits under Proposition 2 (2014).

Increasing or decreasing tax revenues also can be accomplished by changing the basic tax structure—most notably by increasing or decreasing tax rates directly. In California, whether changing the basic tax structure or tax expenditures, increasing state tax revenues generally requires either (a) a two-thirds vote of each house of the Legislature (along with the Governor’s signature or a veto override) or (b) voter approval of a constitutional amendment or initiative statute.