California's extensive budget-balancing toolkit

Governor's May Revision to be released on Friday, May 12

The Governor will release his revised budget proposal, as required by state law, on Friday, May 12. The administration is expected to lower the General Fund tax revenue estimates it released in January, including revenue estimates for 2021-22, 2022-23, and perhaps some or all of the following fiscal years through 2026-27.

The changes to the revenue estimates are likely to lower the estimated Proposition 98 minimum guarantee for schools in some fiscal years. The roughly $20 billion “budget problem” identified by the administration in January—the amount of corrective budget actions needed to bring the 2023-24 state budget into balance—likely will grow.

As discussed below, California has more tools available to help balance the state budget than ever before, thanks largely to a decade of cautious budgeting.

Some Perspective

Past Budget Problems Were Much Larger. The overall and the proportional magnitude of this year’s budget problem—likely, even with Friday’s updated estimate—is nowhere close to that of the worst California budgets in years past. In 2009, for example, the Legislature and Governor Schwarzenegger enacted $59.5 billion of corrective budget actions at a time when total General Fund expenditures, just prior to the Great Recession, totaled about $100 billion per year. By contrast, the administration’s January estimate of a $22.5 billion budget problem in 2023 compares to total General Fund expenditures of $163 billion in 2020-21 and $222 billion in 2021-22.

The Toolkit

More Budget Balancing Tools Than Ever Before. Thanks largely to a decade of cautious budgeting, California now has more tools than ever before to balance the state budget. The decisions on which tools to use will result from discussions between the Governor and the Legislature.

Below is a non-exhaustive list of the budget-balancing tools in California’s toolkit:

Reserves. As of January, the administration estimated the state would have $35.6 billion of budgetary reserves on hand during the 2023-24 fiscal year, consisting of balances in several accounts described below.

The $8.5 billion Public School System Stabilization Account (the “Proposition 98 school reserve” created by 2014’s Proposition 2) is available to help school budgets under certain conditions. The main state “rainy day fund,” the Budget Stabilization Account (BSA) created by Proposition 2, had a $22.4 billion estimated balance as of January. In addition, the Governor’s January budget proposal estimated the balance of the state’s basic, discretionary budget reserve, the Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties (SFEU), at $3.8 billion. The Safety Net Reserve, a discretionary reserve created by the Legislature in 2018, had an estimated $900 million balance. The Budget Deficit Savings Account, another discretionary reserve created in 2018, currently has no funds on hand.

Using the Governor’s January revenue estimates, the State Constitution would allow the Legislature and the Governor to access up to $12.6 billion from the BSA for the 2023 budget process, according to a January estimate by the Legislative Analyst’s Office (LAO). Whether to use this reserve and, if so, how much is a key budget issue, as articulated recently in an article by Legislative Analyst Gabe Petek.

Other State Cash: “Fund Shifts” or Internal Borrowing. California, so far as I can tell, recently has benefited from the largest cash balances of any U.S. state in history. This includes the reserves described above, as well as $18 billion of General Fund cash balances and around $55 billion of other funds, as of April 30. These other funds largely consist of the state’s “special funds,” generally tax and fee-supported funds created in law for specific purposes (for example, to administer programs to regulate a specific industry).

Under court precedents, the Legislature has the ability to shift eligible costs to special or other funds or borrow from such funds if the borrowing is determined by the Legislature not to threaten the fundamental purpose for which the fund was created. The Legislature also has approved borrowings from the general state treasury, pursuant to a few different sections of the Government Code and the Public Utilities Code. Internal borrowings from special funds or the state treasury generally have to repaid over time with interest—often at a rate tied to the investment return of the state treasury investment pool.

Revenue Increases. In general, around 50% to 60% of annual tax revenue increases booked to the General Fund are available to help balance the budget, with the rest of the increase principally going to increase the Proposition 98 minimum funding guarantee for schools. Temporary or permanent tax increases—including reducing or eliminating tax credits and deductions known as “tax expenditures”—generally require a two-thirds vote in both houses of the Legislature, while some fee and penalty increases require only a majority vote. The Senate recently released a plan to increase certain business taxes, offset in part by decreasing some taxes for smaller businesses.

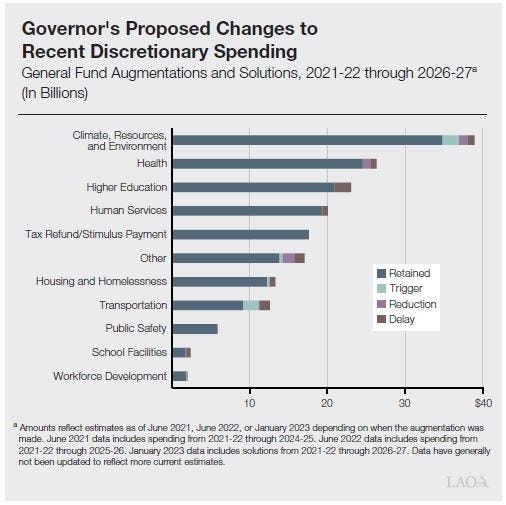

Cutting, Delaying, or “Trigger Cutting” Planned One-Time Expenditures. The Legislature and the Governor have agreed to tens of billions of largely one-time new, discretionary expenditures in the 2021-22 and 2022-23 budgets, as well as in multiyear state budget plans through 2025-26. As shown below in an LAO graphic, the Governor’s January proposal retained around 90% of those expenditures, while proposing to reduce, delay, or “trigger cut” portions of this planned spending (that is, cuts to be triggered if revenue trends in 2023-24 continue to lag). The May Revision or subsequent legislative action may add to or modify these proposed changes for planned one-time expenditures. Focusing reductions or delays on one-time expenditures helps prevent cuts to core, ongoing programs, such as those funding education or health and human services initiatives.

With regard to spending delays, the December 2022 Assembly Budget Blueprint suggested the administration re-evaluate the timing of planned one-time expenditures to shift billions of 2021-2023 expenditures to later years, potentially more accurately reflecting the actual timing of such spending. At the same time, priority projects that are ready to go could still be expedited in the near term.

Temporary or Permanent Reductions to Ongoing Programs. These cuts generally are avoided because people (including state employees), businesses, and organizations often depend on reliable state funding. This year, thankfully, most discussions have revolved around reductions to one-time state budget items, not ongoing funding.

External Borrowing. Infrastructure expenses, in particular, can be funded via external borrowing, in addition to the internal borrowing from the state treasury described above. State facilities often can be funded via tax-exempt or taxable lease revenue bonds approved by the Legislature. Other projects sometimes can be funded from bonds approved by the Legislature and submitted to the voters for approval. In the 2023 budget, some one-time costs could be switched to these types of external borrowing. Bonds generally are repaid over time to investors with a market rate of interest.

Accounting Changes, Etc. Changes to state accounting were used as part of the “wall of debt” during the Great Recession, generally providing non-recurring budget benefits. For example, a shift in the date of booking the June 30 state payroll to July 1 did not affect state employees at all, but saved around $1 billion for the General Fund in one fiscal year. (That amount would be around $1.5 billion today.) That particular accounting change never had to be “paid back,” but the Legislature and Governor nevertheless agreed to fund 13 monthly state payrolls in the 2019-20 budget in order to eliminate the one-day payroll delay and restore the use of this budget management tool for future revenue downturns.

In addition, it is always important to note that the Legislature can propose deleting some of the administration’s proposed expenditures to make room for other expenditures that Assemblymembers and Senators prefer.